You can’t blame literati and producers for going back to the well of British history and literature to fill yet another entertainment bucket with tales both fictional and and non. The stuff just plain sells. It’s almost as dependable as stories about Italian mobsters or Nazi’s.

As I write, another version of Jane Austen’s “least sexy” (why are we even talking about “Austen” and “sexy” in the same sentence?) novel has emerged. According to one source, Emma has thus far spawned four films, a BBC series, and a musical. Want more Brits? There’s the Downton Abbey franchise, and around 19 films about Henry VIII. And on and on. I’m not here to try explaining it, just pointing it out.

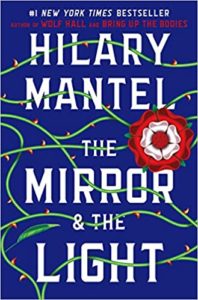

Perhaps the most erudite modern novelization of the Henry VIII saga is Hilary

Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, of which The Mirror and the Light is the final volume (Bringing Up The Bodies is the third). All three books follow the career of Thomas Cromwell, a commoner who rose from a street urchin to Henry’s most trusted advisor. He was even honored with the Order of the Garter and an Earldom along the way. It was a long distance from pouring animal piss on hides in a tannery to scratching out execution orders in the privy council. Mantel takes us into every corner of Cromwell’s mind and heart as we follow his machinations and manipulations, operating always at Henry’s behest (sometimes playing the tricky game of anticipating his wishes) and managing to do pretty well for himself along the way.

It’s a gigantic undertaking, this story that Mantel spins so ably. Two flaws from my point of view, though. First–and this is especially true of the The Mirror and The Light (great title, by the way), it’s too dense and long. The characters and their titles and families are so numerous and intertwined it becomes somewhat like reading–and even being expected to remember–the lists of “begats” in Genesis. Not enough fingers and toes in the known world to accommodate a census of that magnitude. Thus, when someone’s cousin, who was a duke when we last met him, but who is now an earl, or his wife, who was a poor widow a few pages back, suddenly turns up at court with a fancy veil and a train of ladies. . . Well, maybe it’s just me.

Then there are the last thirty or forty pages. I truly like and admire Mantel’s Cromwell, and I think his execution is among the least justified of all the bloodletting in the ten years the book covers. But Mantel’s description of his final days is tantamount to a Wagnerian opera’s last movement. Will the fat lady ever, ever die? Mercifully, she finally does, and a beautifully described conclusion it is, too. It just takes soooo long to get there.

It’s fascinating and amazing to see how deftly Cromwell sets factions against one another, gets them accused of treason, then arranges for their executions. The pattern is as regular as English rain–always either falling or imminent. As a reader, you’re intrigued by how he does it over and over. Intrigued especially because Mantel’s Mann Booker prize-winning prose is so luxuriant, yet spare. Read for example this passage describing how poor Ann of Cleves, the German maid whom Henry greatly regrets marrying, lives waiting for Henry to decide her fate. Will she be allowed to go home to papa, or will her head roll like Anne Boleyn’s?

“She Pretends all is well but she is like a jackdaw waiting for figs to ripen, living on hope.”

There are hundreds of such poetic moments in this monumental work. For all the brutality he arranges, Cromwell himself is a complex character, who is sympathetic when he can be, and we readers are on his side all along. He treats his family well, helps many who come from low backgrounds like his own to gain income and stations in life even while he helps others to their graves. The whole matter of Catholicism vs. the Church of England winds through all this, of course. Henry’s entire adult life is dominated by his battles with the Pope and his minions. Henry’s first wife, the Spaniard Catherine of Aragon, was the occasion for the split between Canterbury and Rome in the first place. How different history might have been had the Pope granted Henry that divorce. That particular Catherine was lucky to escape back to Spain with her religion and her body intact. Not so lucky was her daughter, Mary Tudor, who remained a virtual prisoner in England and remained as well a loyal Catholic who went about slaughtering protestants right and left when she succeeded Henry and became the tyrant-queen known as “Bloody Mary.”

But for all his successes, which went on for ten years or so, Cromwell could escape neither the stigma of his humble origins nor the enmities of the families who were left behind when the axe fell not only on the queens such as Anne Boleyn, but on those decapitated for supposedly associating (consorting) with her. The target on his commoner’s back became bigger and bigger with each spurt of arterial blood.

As servants of our current president have discovered, the hand that holds out treats can also wield a blade. To Mantel’s Cromwell, the end comes as a surprise, despite that he falls to exactly the kind of betrayal and intrigue he himself has arranged dozens of times. He helped Henry arrange his parade of wives in a way that enriched both Henry and England. But when he brought in Ann of Cleves with her body–slack breasts and soft belly–so repugnant that Henry couldn’t do his office to produce an heir, Cromwell was done. Henry did later manage a productive visit or two with Jayne Seymour, which gave us the boy-king Edward VI, followed by the infamous Mary Tudor, followed in turn by the iconic Elizabeth I. Perhaps Hilary will keep her string going and give us her take on the Virgin Queen next. That I would like to read.