Blindspotting is among the top movie experiences of my life. That includes such triumphs as The Seventh Seal and The Godfather. What makes it so?

There is no better answer to that question than is contained in a recent homily by Father Steve Keplinger of Grace St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Tucson. (http://gsptucson.tumblr.com/post/177945930259/fr-steves-sermon-for-sunday-sept-9-2018) Without going into detail as to how our paths crossed, I will simply say that the paths were not long, though they were a little convoluted and indirect. What’s important is that what Father Steve, my friend, Bill Roeske, and I saw in this film was a painful and ugly explanation for the stereotyping and racism that too often dictate our thoughts and actions.

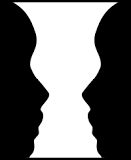

I won’t explore and explain the themes, plot and characters here. I’m going to skim over those and dive right into the deep waters of what this portends for our lives. The film’s title has its origins in concept one of the main characters is studying in her psychology class and demonstrates that we are physically and psychologically incapable of simultaneously seeing two realities at once within the same image. Thus, we can perhaps see below either a vase or two faces looking at one another. We cannot see both at once.

Thus it is that we cannot look at another person and see both a saint and a sinner, a criminal and a minion of the law. Or to further complicate the situation, a black person/criminal and a black person/upstanding citizen. Yet, we deal with these realities every day, and what you might call cognitive dissonance keeps us from appreciating and understanding them. Everything about Blindspotting helps us experience this situation, and it’s not a pleasant experience. The pain, danger, and injustice we visit upon one another because of this inherent disability is enormous. It’s one thing to be told about it and to recognize it intellectually, it’s quite another to see and understand it in depth the way this film forces us to do.

Thus it is that we cannot look at another person and see both a saint and a sinner, a criminal and a minion of the law. Or to further complicate the situation, a black person/criminal and a black person/upstanding citizen. Yet, we deal with these realities every day, and what you might call cognitive dissonance keeps us from appreciating and understanding them. Everything about Blindspotting helps us experience this situation, and it’s not a pleasant experience. The pain, danger, and injustice we visit upon one another because of this inherent disability is enormous. It’s one thing to be told about it and to recognize it intellectually, it’s quite another to see and understand it in depth the way this film forces us to do.

Father Steve’s homily pleads with his audience to recognize and attempt to overcome the human tendencies of Blindspotting, and he evinces some optimism that is possible to do so. He chooses as a scriptural example the parable of Jesus’ treatment of the Canaanite woman from St. Matthew, wherein the prophet recognizes his own racist assumptions and changes his attitude. Father Steve seems to me to suggest that the narrative shows that we are all capable of reform just as Jesus was.

However, I can’t help thinking about how a generation or so later, St. Paul finds it necessary to admonish the Roman Christians to change their ways and to start admitting perviously-excluded gentiles into their ranks. Part of that appeal was strategic, I suppose. The church could not grow and survive if they continued drawing members only from their limited circle. However, I think it was mostly a matter of Early Christian blindspotting that did not allow the folks within that insulated community to see both Roman citizens and sincere Christians in the same person or group.

A couple of thousand years later, we’re still at it. Both the racism and the struggle to reform. Like life itself, the struggle to achieve the goal is often seemingly futile. When asked what a particular poem meant, T.S. Eliot is said to have answered by reading the poem itself aloud. The meaning, he was pointing out, is in the experience, not outside of it. You’ve got to see it to understand it. And like life itself, like the wonderfully poetic rap that is at the center of the film’s epiphany, Blindspotting tells us to keep struggling and, somehow, keep laughing and rapping and writing poems the while.